At Little River, we are proud to only offer a nearly exclusive selection of vegetable dyed rugs. Less than 3% of rug production uses vegetable dyes. (We say 'nearly' because we cannot guarantee that our Indian Zamin or Tibetan Gaun Production is 100% vegetable dye; often those rugs are a mix of yarns colored in both the traditional vegetable method and also with chrome/synthetic dyes.) ALL of our Pakistani / Afghan rugs are vegetable dye.

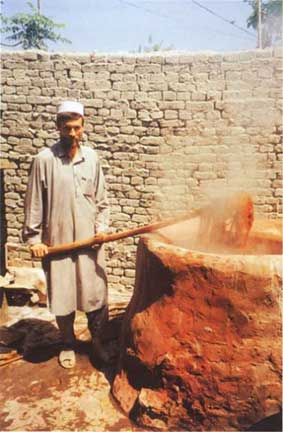

Vegetal dyeing is an art form unto itself, before the weaving even takes place; there are many variables involved - even plants from the same geographical area, gathered at different times of the year can produce varying shades due to seasonal changes.

Vegetal dyeing is an art form unto itself, before the weaving even takes place; there are many variables involved - even plants from the same geographical area, gathered at different times of the year can produce varying shades due to seasonal changes.

Prior to the mid 19th century, many of the weaver's color choices were dictated by the availability of certain plants in their region or what could be obtained by trade. Before the seminal year of 1860, when chemical dyes first arrived on the scene, plant based dyes were all that were available. These dyes are called vegetable dyes or natural dyes and have a distinct look about them. They age beautifully, work harmoniously together and the indigo dye, which creates all the ranges of blue, even preserves the wool. Usually with vegetable dyes one can observe a slight variation in the color itself. Also affecting this is the type of wool being used and how it was spun. Hand-spun wool, being less perfectly formed, will accept the colors of the dyes at different rates of the same shade and will show more variation in color than machine spun wool. Deeply saturated wool will also show less color variation which will only appear after the rug begins to age. This variation of color is termed "abrash" and adds a certain artistic quality and charm to tribal rugs which is often highly regarded.

More recently, new production using vegetable dyes and hand-spun wool has begun to appear in various areas. Started in Turkey in the 1980's by a government sponsored program called DOBAG, Iran quickly followed with tribal weavers in Southern Iran creating new rugs in traditional designs. A number of countries have now reverted back to the traditional methods so there are currently some wonderful rugs available that prior to the last couple of decades could only have been found as antiques.

A good vegetable-dyed rug lights up a room and brings it alive. In addition, the natural dyes are believed to be more durable and light-fast than any of the chemical or aniline dyes. Our customers often comment that our natural-dyed rugs have "character." We would agree!

Progression from initial dye bath to depleted dye bath

shades of:

Natural Indigo

Natural Indigo + Asbarg

(overdyed)

Asbarg Flowers

Pomegranate Rind

Tesu Flowers

Walnut Bark

Madder Roots

Interested in vegetable dyeing your own wool? Go Here

And here are some 'recipes' from Pakistan:

0.25 kg pulverised Walnut bark

Soak the pulverised walnut bark overnight in 20 times its

weight of water.

Boil the soaked walnut bark decoction for at least one hour then

pass it through a sieve and allow to cool. This is the dye bath.

Add the damp, mordanted yarn to the dye bath

Bring to boil in half an hour, Boil for 1 hour.

Allow to cool. Wash, rinse thoroughly and hang to dry.

You can use the remaining dye-bath to make lighter shades.

To dye Yellow with TESU flowers:

0.2 kg dried TESU flowers

Soak the flowers in cold water overnight to extract the cold-water-soluble yellow colouring matter; Strain out the flowers as they also have a pink dye.

Heat the yellow solution obtained over-night to luke warm temperature. Add the damp, mordanted yarn to this dye bath.

Bring to boil in half an hour; Boil the yarn for half an hour

Remove the yarn. Wash it thoroughly and hang to dry.

You can use the remaining dye-bath to make lighter shades.

To dye a strong lacquer red with MADDER roots:

1 kg pulverized madder roots

A little chalk

100 g cream of tartar

200 g glauber's salt

Soak the madder overnight in ample water

Mordant the yarn with Alum

Mix the cream of tartar and glauber's salt in some warm water

Add the chalk to the dye-bath and mix thoroughly

Add the soaked madder to the dye-bath

Slowly heat the dye-bath to luke-warm temperature

Add the damp, mordanted yarn to the bath

Take 2 to 3 hours to bring the dye-bath to simmer

SIMMER till the desired shade is obtained

Add the cream of tartar and glauber's salt to the dye-bath

Simmer for another 30 minutes

Allow to cool

Rinse thoroughly and hang to dry

You can use the remaining dye-bath to make lighter shades.

Vegetable Dyeing Techniques....

Common vegetable dyes

The most commonly used vegetable dyes are indigo (originally obtained by extracting and fermenting indican from the leaves of the indigo plant), madder (produced by boiling the dried, chunked root of the madder plant in the dye pot), and larkspur (produced by boiling the crushed leaves, stems, and flowers of the larkspur plant). These dyes produce, respectively, dark navy blue, dark rusty-red, and muted gold. Long ago dyers realized that as more wool was dyed in a single dyepot, colors became weaker and weaker. Dyers use this notion of depleated dyes to their advantage. The first dyeing produces a deep, strong color. Subsequent dyeings in the same dyepot produce lighter, softer colors (like the three shades of indigo, madder, and yellow illustrated here):

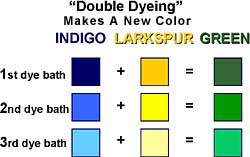

Dyers also quickly learned to combine colors to produce different hues. There is, for instance, no "vegetable" dye material that yields green (an important color if you're interested in weaving a floral design!). First dyeing wool blue, then dyeing it again with yellow, does produce a green color. If you look closely at the green color in a vegetable-dyed rug, you will commonly see that the color is uneven, more blue-green in some areas, and more yellow-green in others. This is because of the double-dyeing technique:

So, by using the notion that depleted dyes produce different hues, and by combining some dyes through overdyeing wool, dyers can produce a large pallette of colors from a very limited variety of materials.